Remote Sim2Real for Dexterous In-Hand Manipulation

Transferring Dexterous Manipulation from GPU Simulation to a Remote Real-World TriFinger

Arthur Allshire, Mayank Mittal, Varun Lodaya, Viktor Makoviychuk, Denys Makoviichuk, Felix Widmaier, Manuel Wüthrich, Stefan Bauer, Ankur Handa, Animesh Garg.

Paper, Project

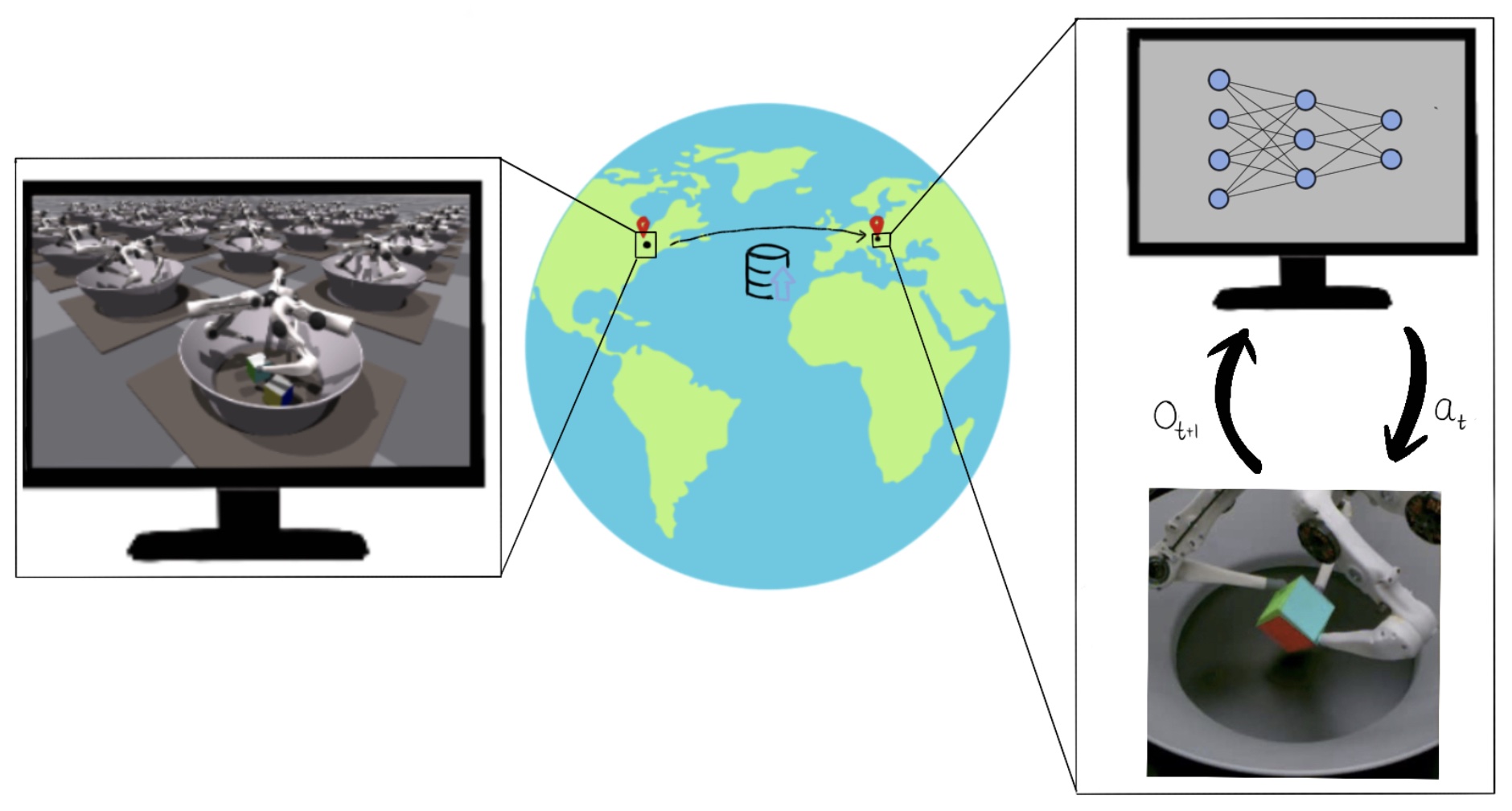

Figure: We have shown that large scale GPU-based simulation can be used to empower robot learning in simulation, and such solutions can be transferred to real robots without the need for physical access to the robots.

Motivation

1. Typical robotics solutions take weeks, if not months, to develop and test

A critical question when designing a Machine Learning based solution is “what is the resource cost of developing this solution?”. There are typically many factors that go into answering this: time, developer skill, and computing resources. It’s rare that a researcher can maximize all of these aspects, hence optimizing the solution development process is critical. This problem is further aggravated in robotics since each task typically requires a completely unique solution that involves a non-trivial amount of hand-crafting from an expert!

Dexterous multi-finger object manipulation has been one of the long-standing challenges in control and learning for robot manipulation [Okamura et al 2001., Sundaralingam et al. 2018, Kumar et al. 2016, Zhu et al. 2018]. While challenges in high-dimensional control for locomotion as well as image based object manipulation with simplified grippers have made remarkable progress in the last 5 years, Multi-finger Dexterous Manipulation remains a high-impact yet hard-to-crack problem. This challenge is due to a combination of issues:

- High-dimensional coordinated control,

- Inefficient simulation platforms,

- Uncertainty in observations and control in real-robot operation, and

- Lack of robust and cost-effective hardware platforms.

These challenges coupled with lack of availability of large scale compute and robotic hardware has limited diversity among the teams attempting to address these problems.

Our goal in this effort is to present a path for democratization of robot learning and a viable solution through large scale simulation and robotics-as-a-service. We focus on 6-DoF object manipulation by using a dexterous multi-finger manipulator as a case study. We show how large-scale simulation done on a desktop grade GPU and cloud-based robotics can enable roboticists to perform research in robotic learning with modest resources.

While a number of efforts in in-hand manipulation have attempted to build robust systems [Okamura et al 2001., Sundaralingam et al. 2018, Kumar et al. 2016, Zhu et al. 2018], one of the most impressive demonstrations came a few years ago from a team at OpenAI which built a system termed Dactyl [OpenAI et al.]. It was an impressive feat of engineering to achieve multi-object in-hand reposing with a Shadow Hand. It was remarkable not only for the final performance but also in the amount of compute and engineering effort to build this demo! As per public estimates, it used 13,000 years worth of computing and the hardware itself was costly and yet required repeated interventions! This immense resource requirement effectively prevented others from reproducing this result and as a result building on it.

We show that our systems effort is a path to address this resource inequality, in the sense that a similar result can now be achieved in under a day using a single desktop-grade GPU and CPU.

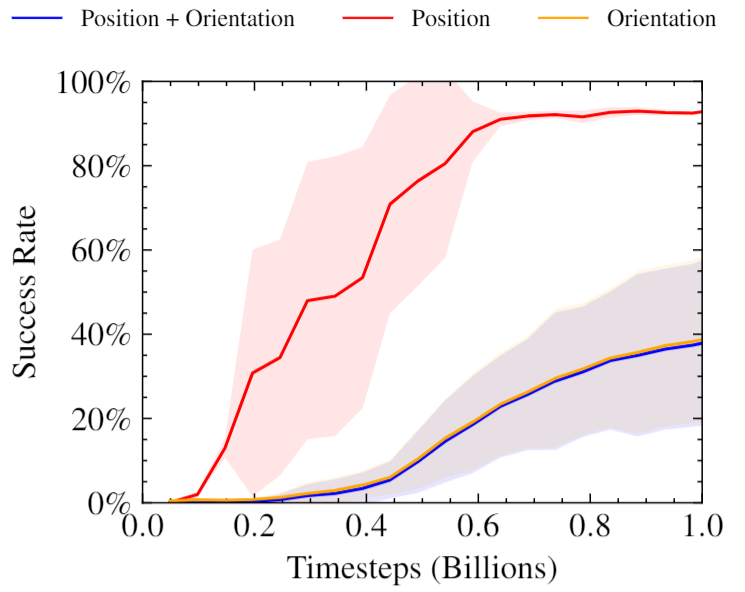

2. The complexity of standard pose representations in the context of Reinforcement Learning

During initial experimentation, we followed previous works [OpenAI et al, 2018, Liang et al, 2018] in providing our policy with observations based on a 3-D cartesian position plus a 4-Dimensional quaternion representation of pose to specify the current and target position of the cube, and reward based on L2 norm (position) and angular difference (orientation) between the desired and current pose of the cube. We found this approach to produce unstable reward curves which was good at optimising the position portion of the reward, even after adjusting relative weightings.

Training curves on the Trifinger manipulation task using a reward function similar to previous wokrs. The nature of the reward makes it very difficult for the policy to optimize, particularly achieving an orientation goal.

Prior work has shown the benefits of alternate representations of spatial rotation when using neural networks [Zhou et al, 2020]. Furthermore, it has been shown that mixing losses this way can lead to collapsing towards only optimising a single objective [Degrave et al. 2020]. The chart implies a similar behaviour, where only position reward is being optimised for.

Inspired by this, we searched for a representation of pose in SO(3) for our 6-DoF reposing problem, which would also naturally trade off position and rotation rewards in a way suited to optimisation via reinforcement learning.

3. Closing the sim2real gap with remote robots

The problem of access to physical robotic resources was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Those fortunate enough to previously have access to robots in their research groups found that the number of people with physical access to the robots was greatly decreased; those that relied on other institutions to provide the hardware were often alienated completely due to physical distancing restrictions.

Our work demonstrated the feasibility of a Robotics as-a-Service (RaaS) approach in tandem with robot learning, where a small team of people (something about maintaining the robot) and a separate team of researchers were able to upload a trained policy remotely collect data for post-processing.

While our team of researchers was primarily based in North America, the physical robot was located in Europe, and so for the duration of the project, our development team was never able to physically be in the same room as the robots we were working on. Remote acces meant we could not vary the task at hand to make it easier, and limited the kinds of iteration and experiments we could do. For example, a priori system identification was not possible as our policy ran on a randomly chosen robot in the entire farm.

We found that despite the lack of physical access, we were able to produce a robust and working policy to solve the 6 Degree-of-Freedom reposing task through a combination of several techniques: Realistic GPU-accelerated simulation, model-free RL, domain randomisation, and task-appropriate representation of pose.

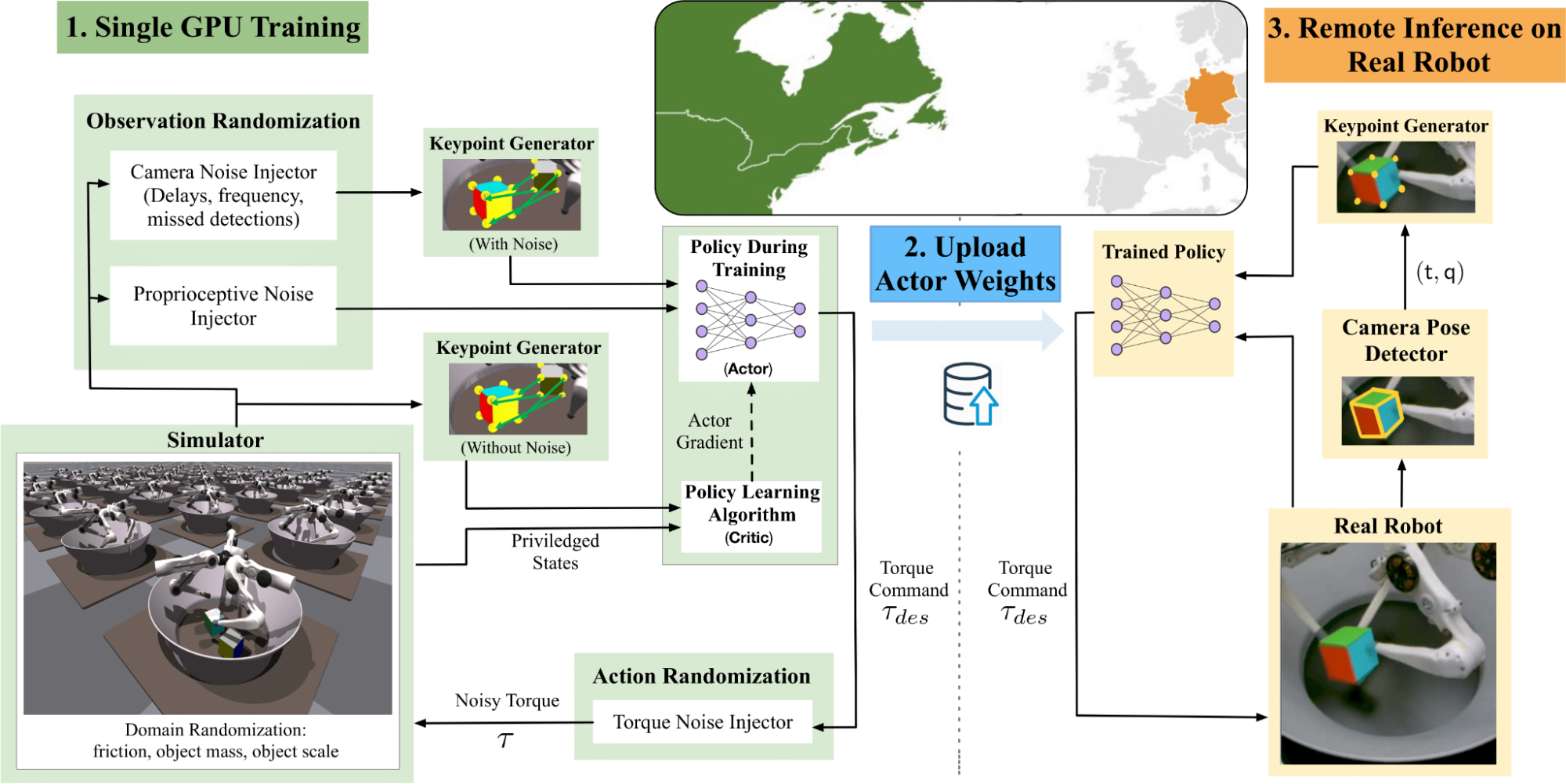

Method Overview

Our system trains using the IsaacGym simulator on 16,384 environments in parallel on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 or RTX 3090 GPU. Inference is then conducted remotely on a TriFinger robot located across the Atlantic in Germany using the uploaded actor weights. The infrastructure on which we perform Sim2Real transfer is provided courtesy of the organisers of the Real Robot Challenge.

Our system trains using the IsaacGym simulator on 16,384 environments in parallel on a single NVIDIA Tesla V100 or RTX 3090 GPU. Inference is then conducted remotely on a TriFinger robot located across the Atlantic in Germany using the uploaded actor weights. The infrastructure on which we perform Sim2Real transfer is provided courtesy of the organisers of the Real Robot Challenge.

1. Collect and process training examples

Using the IsaacGym simulator, we gather high-throughput experience (~100K samples/sec on an RTX 3090). The sample’s object pose and goal pose are to 8 key points of the object’s shape, and domain randomizations are applied to the observations, and environment parameters in order to simulate variations in the proprioceptive sensors of the real robots and cameras. These observations, along with some privileged state information from the simulator, were then used to train our policy.

2. Train policy

Our policy is trained to maximize a custom reward using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm (Schulman et al., 2017). Our reward incentivizes the policy to balance the distance of the robot’s fingers from the object, the speed of movement, and the distance from the object to a specified goal position to solve the task efficiently, despite being a general formulation applicable broadly across in-hand manipulation applications. The policy outputs the torques for each of the robot’s motors, which are then passed back into the simulation environment.

3. Transfer Policy to real robot and run inference

Once we have trained a policy, we upload it to the controller for the real robot. The cube is tracked on the system using 3 cameras. We combine proprioceptive information available from the system along with the converted keypoints representation to provide input to the policy. We repeat the camera-based cube-pose observations for subsequent rounds of policy evaluation to allow the policy to take advantage of the higher-frequency proprioceptive data available to the robot. The data collected from the system is then used to determine the success rate of the policy. The tracking system on the robot currently only supports cubes, however this could be extended in future to arbitrary objects.

Results

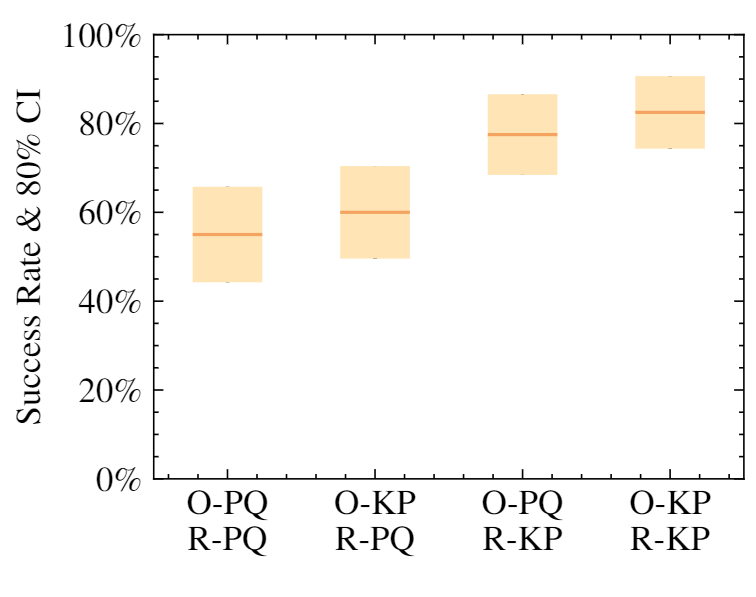

1. The key points representation of pose greatly improves success rate and convergence

.

.

Success Rate on the real robot plotted for different trained agents. O-PQ and O-KP stand for position+quaternion and keypoints observations respectively, and R-PQ and R-KP stand for linear+angular and keypoints based displacements respectively. Each mean made of N=40 trials and error bars calculated based on an 80% confidence interval.

We were able to demonstrate that the policies that used our keypoint representation in either the observation provided to the policy or in reward calculation achieved a higher success rate than using a position+quaternion representation, with the highest performance coming from the policies that used the alternate representation for both elements.

.

.

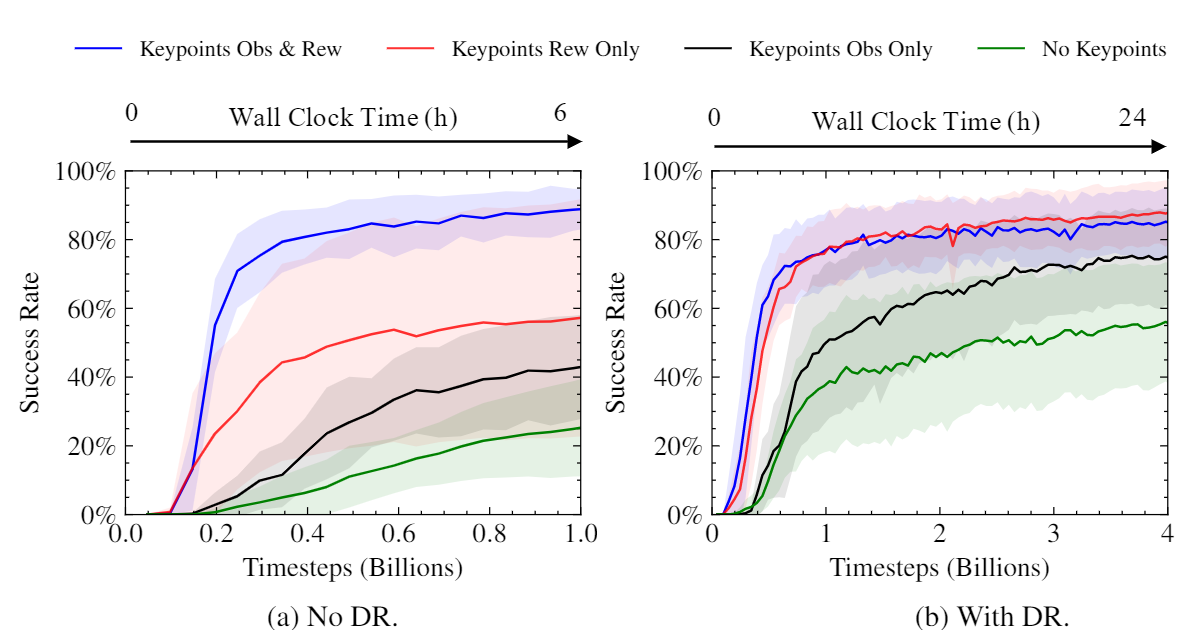

Success Rate over the course of training without and with domain randomization. Each curve is the average of 5 seeds; the shaded areas show standard deviation. Note that training without DR is shown to 1B steps to verify performance; use of DR didn’t have a large impact on simulation success rates after initial training

We performed experiments to see how the use of keypoints impacted the speed and convergence level of our trained policies. As can be seen, using keypoints as part of the reward considerably sped up training, improved the eventual success rate, and reduced variance between trained policies. The magnitude of the difference was surprising to us given the simplicity and generality of using keypoints as part of reward.

2. The trained policies can be deployed straight from the simulator to remote real robots

| Dropping and Regrasping | Recovering from failure |

|---|---|

|

|

The above demonstration displays an emergent behaviour that we’ve termed “dropping and regrasping”. In this maneuver, the robot learns to drop the cube when it is close to the correct position, re-grasp, and pick it back up. This enables the robot to get a stable grasp on the cube in the right position, which leads to more successful attempts. It’s worth noting that this video is in real-time, i.e., it is not sped up in any way.

The robot also learns to use the motion of the cube to the correct location in the arena as an opportunity to simultaneously rotate it on the ground to achieve the correct grasp in challenging target locations far from the center of the fingers’ workspace.

In this demonstration we also see how a poor grasp lead to the cube slipping. Without being explicitly trained to, the robot has learned how to recover from such falls.

Our policy is also robust towards dropping - it is able to recover from a cube falling out of the hand and retrieve it from the ground.

3. Robustness to physics and object variations

We found that our policy was fairly robust to variations in environment parameters in simulation. For example, it gracefully handles scaling up and down of the cube by ranges far exceeding randomization:

| Scaled up cube | Scaled down cube |

|---|---|

|

|

Surprisingly, we found that our policies were able to generalise 0-shot to other objects, for example a cuboid or a sphere:

| Cuboid | Sphere |

|---|---|

|

|

Note that generalisation in scale and object is taking place due to the policy’s own robustness: we do not give it any shape information. The keypoints remain in the same place as they would on a cube:

An example of a successful completion of the manipulation task with the keypoints visualized.

Takeaways and Potentials

Our method shows a viable path for robot learning through large scale GPU-based simulation. We show how it is possible to train a policy using moderate levels of computational resources (desktop-level compute) and transfer to a remote robot. We also show that these policies are robust to a variety of changes in the environment and the object being manipulated. We hope our work can serve as a platform for researchers going forward.

Paper covered in this post

Transferring Dexterous Manipulation from GPU Simulation to a Remote Real-World TriFinger.

Arthur Allshire, Mayank Mittal, Varun Lodaya, Viktor Makoviychuk, Denys Makoviichuk, Felix Widmaier, Manuel Wuthrich, Stefan Bauer, Ankur Handa, Animesh Garg.

Under Review

Acknowledgement: This work was led by University of Toronto in collaboration with Nvidia, Vector Institute, MPI, ETH and Snap. We would like to thank Vector Institute for computing support, as well as the CIFAR AI Chair for research support to Animesh Garg.